انتقل إلى وضع عدم الاتصال باستخدام تطبيق Player FM !

An honest reckoning with Captain Cook’s legacy won’t heal things overnight. But it’s a start

Manage episode 260093565 series 1575188

Captain James Cook arrived in the Pacific 250 years ago, triggering British colonisation of the region. We’re asking researchers to reflect on what happened and how it shapes us today. You can see other stories in the series here and an interactive here.

Editor’s note: This is an edited transcript of an interview with John Maynard for our podcast Trust Me, I’m An Expert. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names of deceased people.

There are a multitude of Aboriginal oral memories about Captain James Cook, right across the continent.

As the research from Deborah Bird Rose shows, many Aboriginal people in remote locations are certainly under the impression that Cook came there as well, shooting people in a kind of Cook-led invasion of Australia. Many of these communities, of course, never met James Cook; the man never even went there.

But the deep impact of James Cook that spread across the country and he came to represent the bogeyman for Aboriginal Australia.

Even back in the Protection and Welfare Board days, a government car would turn up and Aboriginal people would be running around screaming, “Lookie, lookie, here comes Cookie!”

I wrote about Uncle Ray Rose, sadly recently departed, who’d had a stroke. Someone said, “How do you feel?” And he said, “No good. I’m Captain Cooked.”

Cook, wherever he went up the coast, was giving names where names already existed. Yuin oral memory in the south coast of NSW gives the example of what they called Gulaga and Cook called “Mount Dromedary”:

[…] that name can be seen as the first of the changes that come for our people […] Cook’s maps were very good, but they did not show our names for places. He didn’t ask us.

Cook has been incorporated into songs, jokes, stories and Aboriginal oral histories right across the country.

Why? I think it’s an Aboriginal response to the way we’ve been taught about our history.

Myth-making persists but a shift is underway

I came through a school system of the 50s and 60s, and we weren’t weren’t even mentioned in the history books except as a people belonging to the Stone Age or as a dying race.

It was all about discoverers, explorers, settlers and Phar Lap or Don Bradman. But us Aboriginal people? Not there.

We had this high exposure of the public celebration of Cook, the statues of Cook, the reenactments of Cook – it was really in your face. For Aboriginal people, how do we make sense of all of this, faced with the reality of our experience and the catastrophic impact?

We’ve got to make sense of it the best way we can, and I think that’s why Cook turns up in so many oral histories.

I think wider Australia is moving towards a more balanced understanding of our history. Lots of people now recognise the richest cultural treasure the country possesses is 65,000 years of Aboriginal cultural connection to this continent.

That’s unlike anywhere else in the world. I mean no disrespect, but 250 years is a drop in a lake compared to 65,000 years. From our perspective, in fact, we’ve always been here. Our people came out of the Dreamtime of the creative ancestors and lived and kept the Earth as it was in the very first day.

With global warming, rising sea levels, rising temperatures and catastrophic storms, Aboriginal people did keep the Earth as it was in the very first day to ensure that it was passed to each surviving generation.

There was going to be a (now-cancelled) circumnavigation of Australia in the official proceedings this year, which the prime minister supported. But James Cook didn’t circumnavigate Australia. He only sailed up the east coast. So that’s creating more myths again, which is a senseless way to go.

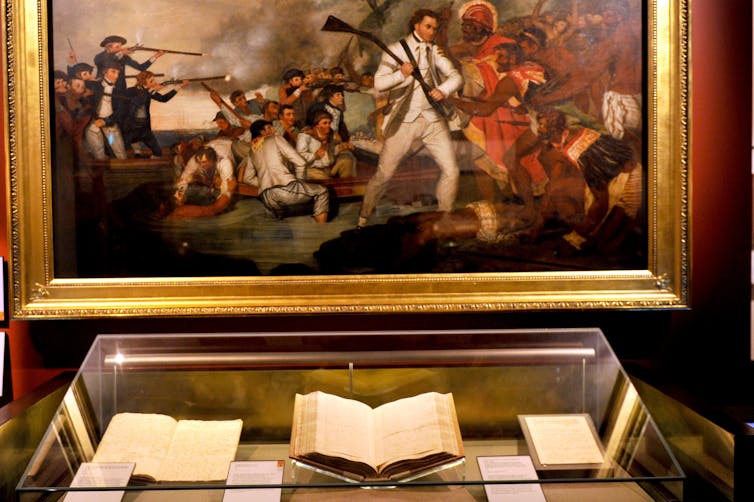

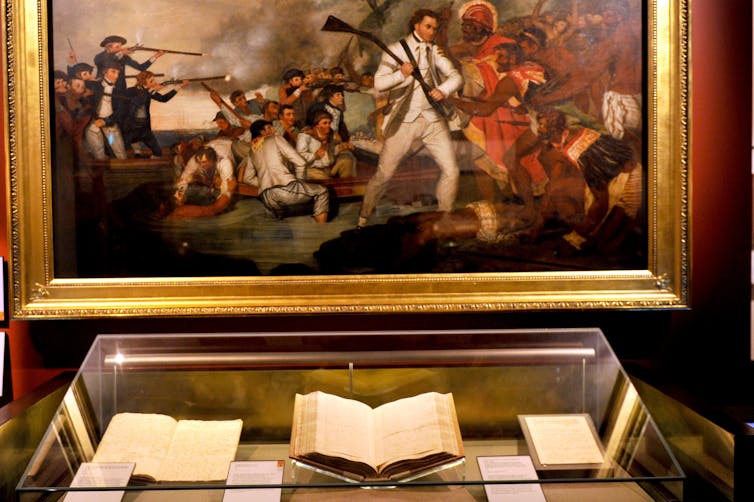

‘With the consent of the Natives to take possession’

Personally, I have high regard for James Cook as a navigator, as a cartographer, and certainly as an inspiring captain of his crew. He encouraged incredible loyalty among those that sailed with him on those three voyages. And that has to be recognised.

But against that, of course, is the reality that he was given secret instructions by the Navy to:

With the consent of the Natives to take possession of the convenient situations in the country in the name of the king of Great Britain.

Well, consent was never given. When they went ashore at Botany Bay, two Aboriginal men brandished spears and made it quite clear they didn’t want him there. Those men were wounded and Cook was one of those firing a musket.

There was no gaining any consent when he sailed on to Possession Island and planted that flag down. Totally the opposite, in fact.

And the most insightful viewpoint is from Cook himself, who wrote that:

all they seem’d to want was for us to be gone.

Cook’s background gave him insight

James Cook wasn’t your normal British naval officer of that time period. To get into such a position, you normally had to be born into the right family, to come from money and privilege.

James Cook was none of those things. He came from a poor family. His father was a labourer. Cook got to where he was by skill, endeavour, and, unquestionably, because he was a very smart man and brilliant at sea. But it’s also from that background that he’s able to offer insight.

There’s an incredible quotation of Cook’s where he says of Aboriginal people:

They live in a Tranquillity which is not disturb’d by the Inequality of Condition… they live in a warm and fine Climate and enjoy a very wholsome Air.

Now, Cook is comparing what he is seeing in Australia with life back Britain, where there is an incredible amount of inequality. London, at the time, was filthy. Sewerage pouring through the streets. Disease was rife. Underprivilege is everywhere.

In Australia, though, Cook sees what to him looks like this incredible egalitarian society and it makes an impact on him because of where he comes from.

But deeper misunderstandings persisted. In what’s now called Cooktown there are, at first, amicable relationships with the Guugu Yimithirr people, but when they come aboard the Endeavour they see this incredible profusion of turtles that the crew has captured.

They’re probably thinking, “these are our turtles.” They would quite happily share some of those turtles but the Bristish response is: you get none.

So the Guugu Yimithirr people go off the ship and set the grass on fire. Eventually, there’s a kind of peace settlement but the incident reveals a complete blindness on the part of the British to the idea of reciprocity in Aboriginal society.

Read more: 'They are all dead': for Indigenous people, Cook's voyage of 'discovery' was a ghostly visitation

A collision of catastrophic proportions

The impact of 1770 has never eased for Aboriginal people. It was a collision of catastrophic proportions. The whole impact of 1788 – of invasion, dispossession, cultural destruction, occupation onto assimilation, segregation – all of these things that came after 1770.

Anything you want to measure – Aboriginal health, education, employment, housing, youth suicide, incarceration – we have the worst stats. That has been a continuation, a reality of the failure of government to recognise what has happened in the past and actually do something about it in the present to fix it for the future.

We’ve had decades and decades of governments saying to us, “We know what’s best for you.” But the fact is that when it comes to Aboriginal well being, the only people to listen to are Aboriginal people and we’ve never been put in the position.

We’ve been raising our voices for a long time now, but some people see that as a threat and are not prepared to listen.

An honest reckoning of the reality of Cook and what came after won’t heal things overnight. But it’s a starting point, from which we can join hands and walk together toward a shared future.

A balanced understanding of the past will help us build a future – it is of critical importance.

New to podcasts?

Everything you need to know about how to listen to a podcast is here.

Additional audio credits

Kindergarten by Unkle Ho, from Elefant Traks.

Marimba On the Loose by Daniel Birch, from Free Music Archive.

Podcast episode recorded and edited by Sunanda Creagh.

Lead image

Uncle Fred Deeral as little old man in the film The Message, a film by Zakpage, to be shown at the National Museum of Australia in April. Nik Lachajczak of Zakpage.

52 حلقات

Manage episode 260093565 series 1575188

Captain James Cook arrived in the Pacific 250 years ago, triggering British colonisation of the region. We’re asking researchers to reflect on what happened and how it shapes us today. You can see other stories in the series here and an interactive here.

Editor’s note: This is an edited transcript of an interview with John Maynard for our podcast Trust Me, I’m An Expert. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names of deceased people.

There are a multitude of Aboriginal oral memories about Captain James Cook, right across the continent.

As the research from Deborah Bird Rose shows, many Aboriginal people in remote locations are certainly under the impression that Cook came there as well, shooting people in a kind of Cook-led invasion of Australia. Many of these communities, of course, never met James Cook; the man never even went there.

But the deep impact of James Cook that spread across the country and he came to represent the bogeyman for Aboriginal Australia.

Even back in the Protection and Welfare Board days, a government car would turn up and Aboriginal people would be running around screaming, “Lookie, lookie, here comes Cookie!”

I wrote about Uncle Ray Rose, sadly recently departed, who’d had a stroke. Someone said, “How do you feel?” And he said, “No good. I’m Captain Cooked.”

Cook, wherever he went up the coast, was giving names where names already existed. Yuin oral memory in the south coast of NSW gives the example of what they called Gulaga and Cook called “Mount Dromedary”:

[…] that name can be seen as the first of the changes that come for our people […] Cook’s maps were very good, but they did not show our names for places. He didn’t ask us.

Cook has been incorporated into songs, jokes, stories and Aboriginal oral histories right across the country.

Why? I think it’s an Aboriginal response to the way we’ve been taught about our history.

Myth-making persists but a shift is underway

I came through a school system of the 50s and 60s, and we weren’t weren’t even mentioned in the history books except as a people belonging to the Stone Age or as a dying race.

It was all about discoverers, explorers, settlers and Phar Lap or Don Bradman. But us Aboriginal people? Not there.

We had this high exposure of the public celebration of Cook, the statues of Cook, the reenactments of Cook – it was really in your face. For Aboriginal people, how do we make sense of all of this, faced with the reality of our experience and the catastrophic impact?

We’ve got to make sense of it the best way we can, and I think that’s why Cook turns up in so many oral histories.

I think wider Australia is moving towards a more balanced understanding of our history. Lots of people now recognise the richest cultural treasure the country possesses is 65,000 years of Aboriginal cultural connection to this continent.

That’s unlike anywhere else in the world. I mean no disrespect, but 250 years is a drop in a lake compared to 65,000 years. From our perspective, in fact, we’ve always been here. Our people came out of the Dreamtime of the creative ancestors and lived and kept the Earth as it was in the very first day.

With global warming, rising sea levels, rising temperatures and catastrophic storms, Aboriginal people did keep the Earth as it was in the very first day to ensure that it was passed to each surviving generation.

There was going to be a (now-cancelled) circumnavigation of Australia in the official proceedings this year, which the prime minister supported. But James Cook didn’t circumnavigate Australia. He only sailed up the east coast. So that’s creating more myths again, which is a senseless way to go.

‘With the consent of the Natives to take possession’

Personally, I have high regard for James Cook as a navigator, as a cartographer, and certainly as an inspiring captain of his crew. He encouraged incredible loyalty among those that sailed with him on those three voyages. And that has to be recognised.

But against that, of course, is the reality that he was given secret instructions by the Navy to:

With the consent of the Natives to take possession of the convenient situations in the country in the name of the king of Great Britain.

Well, consent was never given. When they went ashore at Botany Bay, two Aboriginal men brandished spears and made it quite clear they didn’t want him there. Those men were wounded and Cook was one of those firing a musket.

There was no gaining any consent when he sailed on to Possession Island and planted that flag down. Totally the opposite, in fact.

And the most insightful viewpoint is from Cook himself, who wrote that:

all they seem’d to want was for us to be gone.

Cook’s background gave him insight

James Cook wasn’t your normal British naval officer of that time period. To get into such a position, you normally had to be born into the right family, to come from money and privilege.

James Cook was none of those things. He came from a poor family. His father was a labourer. Cook got to where he was by skill, endeavour, and, unquestionably, because he was a very smart man and brilliant at sea. But it’s also from that background that he’s able to offer insight.

There’s an incredible quotation of Cook’s where he says of Aboriginal people:

They live in a Tranquillity which is not disturb’d by the Inequality of Condition… they live in a warm and fine Climate and enjoy a very wholsome Air.

Now, Cook is comparing what he is seeing in Australia with life back Britain, where there is an incredible amount of inequality. London, at the time, was filthy. Sewerage pouring through the streets. Disease was rife. Underprivilege is everywhere.

In Australia, though, Cook sees what to him looks like this incredible egalitarian society and it makes an impact on him because of where he comes from.

But deeper misunderstandings persisted. In what’s now called Cooktown there are, at first, amicable relationships with the Guugu Yimithirr people, but when they come aboard the Endeavour they see this incredible profusion of turtles that the crew has captured.

They’re probably thinking, “these are our turtles.” They would quite happily share some of those turtles but the Bristish response is: you get none.

So the Guugu Yimithirr people go off the ship and set the grass on fire. Eventually, there’s a kind of peace settlement but the incident reveals a complete blindness on the part of the British to the idea of reciprocity in Aboriginal society.

Read more: 'They are all dead': for Indigenous people, Cook's voyage of 'discovery' was a ghostly visitation

A collision of catastrophic proportions

The impact of 1770 has never eased for Aboriginal people. It was a collision of catastrophic proportions. The whole impact of 1788 – of invasion, dispossession, cultural destruction, occupation onto assimilation, segregation – all of these things that came after 1770.

Anything you want to measure – Aboriginal health, education, employment, housing, youth suicide, incarceration – we have the worst stats. That has been a continuation, a reality of the failure of government to recognise what has happened in the past and actually do something about it in the present to fix it for the future.

We’ve had decades and decades of governments saying to us, “We know what’s best for you.” But the fact is that when it comes to Aboriginal well being, the only people to listen to are Aboriginal people and we’ve never been put in the position.

We’ve been raising our voices for a long time now, but some people see that as a threat and are not prepared to listen.

An honest reckoning of the reality of Cook and what came after won’t heal things overnight. But it’s a starting point, from which we can join hands and walk together toward a shared future.

A balanced understanding of the past will help us build a future – it is of critical importance.

New to podcasts?

Everything you need to know about how to listen to a podcast is here.

Additional audio credits

Kindergarten by Unkle Ho, from Elefant Traks.

Marimba On the Loose by Daniel Birch, from Free Music Archive.

Podcast episode recorded and edited by Sunanda Creagh.

Lead image

Uncle Fred Deeral as little old man in the film The Message, a film by Zakpage, to be shown at the National Museum of Australia in April. Nik Lachajczak of Zakpage.

52 حلقات

كل الحلقات

×مرحبًا بك في مشغل أف ام!

يقوم برنامج مشغل أف أم بمسح الويب للحصول على بودكاست عالية الجودة لتستمتع بها الآن. إنه أفضل تطبيق بودكاست ويعمل على أجهزة اندرويد والأيفون والويب. قم بالتسجيل لمزامنة الاشتراكات عبر الأجهزة.