60 years ago today, they murdered my protector

Manage episode 424814252 series 3540148

Friends,

I’ve shared some of this with you, but today marks 60 years since it happened — when the Klan murdered my protector.

I was always the shortest kid in school, which made me an easy target for bullies. To protect myself, I got into the habit of befriending older boys who’d watch my back.

One summer when I was around 8 years old, while visiting my maternal grandmother at her cabin in the Adirondack Mountains, I found Mickey, a kind and gentle teenager with a ready smile who made me feel safe.

I don’t recall asking Mickey to protect me. He wasn’t the kind of hulking kid I usually chose as protector. He was on the short side and thin. And I don’t remember Mickey putting up any kind of fight to defend me or even quieting the kids who made fun of me.

But I do remember Mickey’s warmth and reassuring presence. He wore a sailor’s cap and seemed forever cheerful. His calm good nature seemed to automatically cast a positive spell over kids who’d otherwise turn to bullying.

We were not friends. I was only eight, and he was a young teenager. Yet I loved him.

Years went by, and I grew into a teenager who no longer needed older boys to protect me from bullies. I lost track of Mickey.

It wasn’t until September of 1964, my freshman year in college, that I heard what had happened to him.

Early that summer, Mickey had traveled to Mississippi to register Black voters.

The Civil Rights Movement was in full bloom. Yet the South remained segregated, especially when it came to voting, where poll taxes, literacy tests, and violence were intended to silence and intimidate Black citizens.

Although about 40 percent of Mississippi’s population was Black, fewer than 7 percent were registered to vote. The system was enforced by white supremacists who could commit crimes with impunity because the entire region had become a one-party state.

“Freedom Summer” of 1964 brought together college students to work with Black people from Mississippi to register Black voters, under the aegis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Mickey — whose full name was Michael Schwerner — was among the first wave of volunteers to arrive in Mississippi.

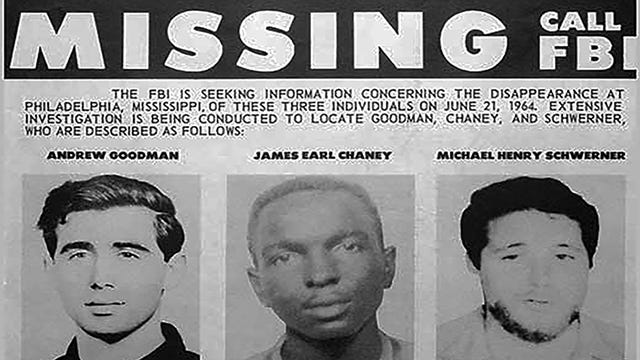

On the afternoon of June 21, 1964 (60 years ago today), while driving near Philadelphia, Mississippi, with two other student volunteers — Andrew Goodman, who was also white, and James Chaney, a young Black man — Mickey was stopped by Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff Cecil Ray Price for allegedly speeding. Price locked them up in the local jail.

That night, after they paid their speeding ticket and left the jail, Price followed them in his police car, stopped them again, ordered them into his car, and took them down a deserted road, where he turned them over to a group of his fellow Ku Klux Klan members.

The group beat Mickey, Goodman, and Chaney. Then they shot them at point-blank range and buried them in an earthen dam. Their bodies weren’t found until August 4.

For weeks, no one knew what had happened to the three missing voting rights volunteers.

Lyndon Johnson used concern over their disappearance to pressure the House to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law on July 2.

On July 16, two weeks after Johnson signed the bill (and more than three weeks after Mickey, Chaney, and Goodman had disappeared), Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater accepted the Republican nomination for president at the Cow Palace in Daly City, California.

Goldwater had voted against the Civil Rights Act. He told Republican delegates that “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And … moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.”

***

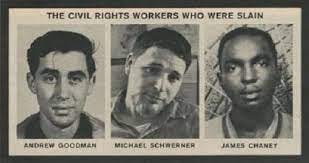

Mickey’s body and those of Chaney and Goodman were found on August 4. They were illustrations of extremism in the defense of what white supremacists defined as liberty.

The state of Mississippi refused to bring murder charges against any of the killers.

Eventually, Price and Neshoba County Sheriff Laurence Rainey, also a Klan member, and 16 others, including Samuel Bowers, the Imperial Wizard of Mississippi’s White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, were arraigned for the federal crime of conspiracy to violate the civil rights of the murdered young men.

An all-white jury found seven of the defendants guilty, including Price and Bowers. After several unsuccessful appeals, each received a sentence of between three and 10 years. Ultimately none would serve more than six years behind bars.

***

When the news reached me that Mickey, who had protected me from childhood bullies, had been murdered by white supremacists — by violent bullies who would stop at nothing to prevent Black people from exercising their right to vote — something snapped inside me.

It was as if I got a new pair of eyes. I began to see everything differently.

Before then, I understood bullying as a few kids picking on me for being short — making me feel bad about myself.

After I learned what happened to Mickey, I began to see bullying on a larger scale, all around me. In Black people bullied by white people. In workers bullied on the job. In girls and women bullied by men. In the disabled or gay or poor or sick or immigrant bullied by employers, landlords, politicians, insurance companies.

I saw the powerful and the powerless, the exploiters and the exploited.

It seemed as if the world had changed, but I had changed. I had a different understanding of the meaning of justice. It became as personal to me as were the bullies who called me names and threatened me in school — but larger, more encompassing, and more urgent.

Sixty years after the Freedom Summer murders, America still wrestles with bullies.

We’ve witnessed a rise in hate crimes targeting people of color, LGBTQ+ people, immigrants, Jews, and Muslims.

Laws that strip Americans of reproductive freedoms.

Laws that target trans people, that ban books, that restrict the right to vote.

Politicians who insult and demean people with disabilities, women, and trans kids.

We must never give in to brutality. It is incumbent on all of us to stand up to bullies — and be each other’s protectors.

17 حلقات